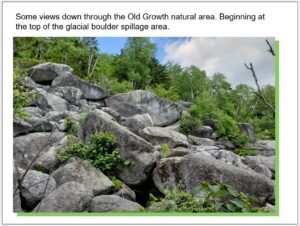

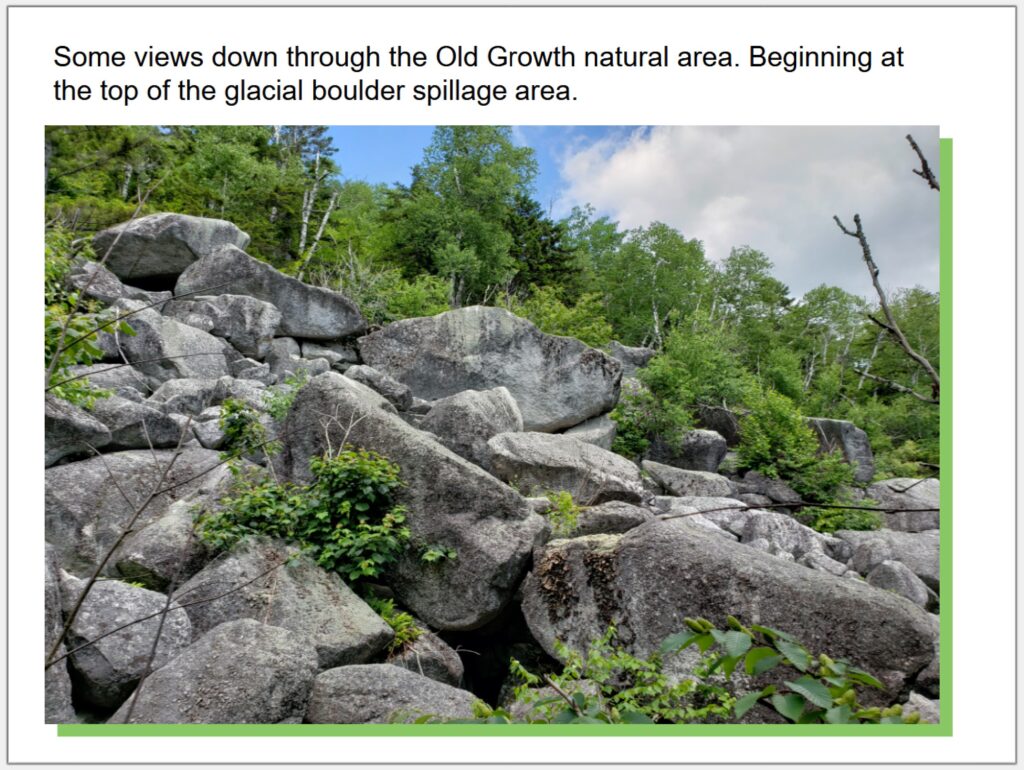

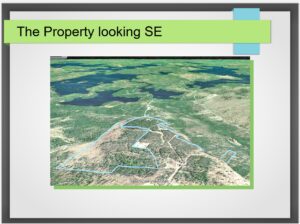

Almanac Mountain stands prominently above wooded and marshy land to the north and south. The geology of Almanac Mountain figures prominently in geological reports of Larrabee et al., 1965, Ayuso 1984, and Ludman and Hopeck 2020. Almanac Mountain hosts the oldest sedimentary rocks in the region. These rocks have been deformed several times in their history. These rocks have been heated by the intrusion of a large granitic complex. The current topography reflects the bedrock geology’s interaction with continental glaciers during the last iceage (Ludman and Hopeck, 2020). Two sedimentary sequences are present in the Almanac Mountain area. The oldest sequence directly underlies and the newer sequence is located near Spaulding Pond to the west. The oldest sequence is part of a geologic terrain called the Miramichi and extends from ~300km northeast in New Brunswick to Greenfield, Maine to the southwest (Fyffe et al., 2011). Ludman and Hopeck, 2020 mapped the rocks underlying the lookout ledge on Almanac Mountain as part of the Baskahegan Lake Formation which is surrounded on the west, north and east by the Bowers Mountain Formation. The Baskahegan Lake Formation is a sandstone and wacke interbedded with subordinate mudstone and shale (Ludman and Hopeck, 2020). At the lookout ledge outcrop it is a rusty weathering mixed sandstone and shale. The Bowers Mountain Formation is described by Ludman and Hopeck 2020 as a thin-bedded, dark, sulfidic shale interbedded with gray shale and minor sandstone. The Miramichi Terrain developed from Late Cambrian to earliest Ordovician (Pickerill and Fyffe, 1999) and has been interpreted as a sedimentary and volcanic island arc in an Ordovician sea. The younger sedimentary rocks in the west side of the Almanac Mountain area are part of the latest Ordovician to Silurian Central Maine/Aroostook-Matapedia belt. Regionally, these rocks contain fragments of the older Miramichi, indicating uplift and erosion of the latter (Ludman and Hopeck, 2020). The Sam Rowe Ridge Formation is exposed west of Almanac Mountain and is composed of thin- to medium-bedded mixed calcareous shale, siltstone, and mudstone. The sandstones and shales at the lookout ledge on Almanac Mountain have been heated and transformed into hardened hornfels by the intrusion of the Passadumkeag River pluton to the south. The thin shale layers have been transformed into biotite and oval cordierite. The sandstone layers have been transformed into hammer-ringing quartzite (Ludman and Hopeck, 2020). Outcrops along the ridge contain angular blocks of hornfels and dikes of granitoid from the pluton. The igneous pluton extends from east and west of Almanac Mountain and south to Passadumkeag Mountain and Nicatous Lake. This igneous intrusion is referred to as the Bottle Lake Complex (Keith, 1933) and has been subdivided into the Passadumkeag River and Whitney Cove plutons by Ayuso 1984. The Passudumkeag River pluton south of and closest to Almanac Mountain contains medium- to course-grained, both porphyritic and equigranular granite and quartz monzonite. It contains biotite and variable amounts of hornblende and has a gray to pinkish gray color. Farther to the south it is distinctly porphyritic with potassium feldspar crystals ranging up to 7cm (Ayuso 1984). The granites and quartz monzonites in the Bottle Lake Complex have been dated at 381Ma, placing it in the middle to upper Devonian (Ayuso et al., 1984). Almanac Mountain’s elevation is 1052’ and is surrounded by lake levels as low as 300’. The metamorphic hardening due to contact metamorphism is responsible for Almanac Mountains prominence. During the iceage, glacial ice with a bedload of sand and cobbles ground the local geology, hollowing out softer, more easily eroded rocks and leaving behind harder rocks. The apparent ice movement direction from NNW to SSE resulted in the distinct shape of Almanac Mountain. It has a shallow incline on the north slope and a steep drop to the south. The steep side has car-size boulders of hornfels and granite from the ridge above. The north slope has glacially polished pavement outcrops. This is typical of the glacial structure roches moutonnées. Lidar images show many examples of roches moutonnées in the Sysladobis Land Owners Association area as well as abundant ice flow direction indicators. Martin Yates, School of Earth and Climate Sciences, University of Maine, Orono, Maine 04469-5790